[Celebration] 3 Writing Lessons From 2 Years On Substack

Celebrating our 20,000 subscribers milestone

This week, we’ll take a second to celebrate our 20,000 subscribers milestone with a few of the lessons I’ve learned along the way. We will be back again next week for more strategies to turbocharge your reading!

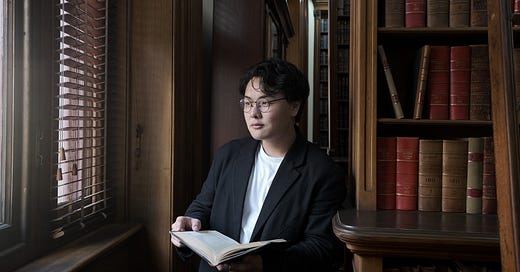

About a week ago, we gained our 20,000th subscriber on this platform. It looked like any other morning: double espresso, an open journal, and an empty page, but that morning not only marked a milestone in our publication’s growth but also two full years of researching, writing, and dancing with words.

Substack has completely changed my life in the same way it has for many writers. It has allowed me to earn a sustainable living, get a book deal with a prestigious publisher, all the while sharpening my craft one post at a time. So, for this week’s post I want to go back and summarise some of the principles behind this amazing community and body of work.

First of all, the word principle here deserves a bit of clarification. In my loosey-goosey definition, it’s simply looking into the what that makes the how work.

I’m sure you don’t need the how if you’re in a position to start writing on Substack (there are plenty of articles for that kind of stuff), but after mentoring a few writers on this platform I noticed that they don’t need any hows but their whats needed a bit of adjusting. So, with that being said, here’s

1: If you’re excited about an idea, you’re not ready to write about it

There are two types of writers under the sun: the idea intolerant and the constipated.

The idea intolerant, like those who have an aversion to lactose, needs to get an idea out as fast as possible. When I first started writing for A Mug of Insights, I was definitely idea intolerant. I wanted to learn something and immediately write about it that afternoon lest the eureka moment disappear. But I usually found myself running out of steam at around the 500-word mark, baking an article with 30% substance and 70% fluff. It took 1 year of writing in sharp starts and stops to finally come to terms with the fact that I simply didn’t have enough to fill up one good, substantial piece of writing if I crank out 3-4 pieces of erratic fluff weekly.

Then things are better over there with the constipated bunch, right? I thought so too, until my girlfriend started her Substack:

. Unlike me, she was definitely a lot slower with the writing part. She planned her metaphors to a tee, read book after book for research and drafted one-liner conclusions that left the readers in awe… All this put my stale journalistic prose to shame, but whenever the blank page paid her a visit, she’d sit frozen in front of the keys as those beautiful ideas clashed with the ugly reality of writing.The way I see it, the idea intolerant and the constipated are two sides of the same coin. Both suffer from having half-baked ideas that get them too excited. The former has no time to fully flesh out an idea in writing, while the latter obsesses with a limited scope that paralyses them from putting down a single word. The result is usually the same: great ideas that struggle to materialise into writing.

I’m not going to throw out a platitude like the answer’s somewhere in the middle, man, because anyone who says that should be banned from breakfasts. Experience, as painful as they were, taught me that the best thing to write about are the things that are so boring that they sound like common sense to you.

You’d be surprised how much you know regardless of your background. For instance, when people sometimes ask me how I go about making my YouTube videos, I’d tell them just to get a camera and start shooting. But then, after a week or so, they’re back with tails between their legs: “My focus is blurry,” one pleads, “the colour’s all off!” another one screams. “My audio sounds like I’m recording from a bathroom,” one calls me when they’re on the John. These instances pointed out again and again that something I took completely for granted (F.1.4 + ISO 250 + 1/50 + 23.976 fps will give you videos that will make you droll) might sound like complete nonsense to people in need.

Same with writing. Some ideas, while they might sound like common sense and boring to you, might just save another fellow years of wrong turns. Better yet, writing about these topics will ensure that your ideas are never half-baked because you’ve been marinating them for years. That’s the first lesson I stand by before I set a single word down on the page: pick a boring topic that you can write a lot about, and watch yourself never run out of ideas.

2: Always place yourself in the background

There’s a deep paradox that exists in the heart of creativity: the more you try to find your voice, the less you’ll sound like yourself.

This gets us into the approach to style that I’ve adopted from E.B. White’s bible: The Elements of Style. His argument is simple: the only way to find your writing style is to place yourself in the background.

When I first started writing, I was writing according to what I thought writing should sound like and called that my voice. If you can’t tell already, A Mug of Insights is heavily inspired by The French Dispatch and The New Yorker. I wanted to construct a carefully researched newsletter complemented by a witty & humorous motif. Yet, this obsession with style made some of my earlier pieces read like texts from that guy who has, with no basis in reality, decided overnight that he will now be a funny person. I was engrossed in the idea of sounding a certain way instead of just listening to what came out in my writing.

Funnily enough, the turning point came when I was writing up my Honours thesis. The first chapter, when subjected to my supervisor’s discerning gaze, turned out to be an absolute disaster. The main problem was precisely what I’ve been struggling with on Substack: writing according to what the writing should sound like instead of employing style to serve readability. My supervisor told me to unclench and guide the reader instead of purposefully confusing them, like how an academic normally would.

Then, I locked myself in the bathroom, took a minute, redrafted the chapter and figured that I enjoyed the writing a lot more with this unclenched style. Before long, I started using the same trick on A Mug of Insights. Instead of worrying about how I sounded on the page, I spent all my nervous energy on how I could guide the reader with a pleasurable reading experience.

Without noticing it at the time, I’ve placed myself in the background and focused solely on ramming one good idea into the reader’s head weekly. This is when The Weekly Column started gaining momentum. People adored the bite-sized ideas, but strange comments like “your writing is so engaging” and “your humour is underrated” started popping up all over my notification board. Naturally, they got into my head, but as soon as I paid attention to my voice, tedious reading and strained writing came straight back like bad acne. It took a few months of back and forth to drill this lesson into my head: focus on communicating effectively, and your style will naturally emerge.

Now, when I write, I cull bad ideas like how an overweight cable producer cancels TV shows: is this an interesting idea for the audience? No? Season 2 is off the table, get out!

But isn’t writing always from personal experience? How can you completely erase yourself from your writing? I’m glad you asked. This brings me to another lesson:

3: Only write 10% of what you’ve experienced

“Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte”, wrote Pascal to a friend, which translates to something like: “I’d make this letter shorter if I had the time”.

We are all armed with experiences and fun stories we’d love to render into writing, but deciding what makes it onto the page takes a lot of discipline. When I started writing here, I jammed all sorts of nonsense stories just to convince people that I’m an interesting person. “I played pool at this pub and this guy kept trying to…” What’s your point?

But as I read more and rearranged my marbles a bit, I noticed how disciplined good writers are with their anecdotes. I’m currently reading Mark Forsyth’s A Short History of Drunkenness, and a small detail: "as a result, 500,000 generations later, your descendant, staggering home from the pub, decides that they’d kill for a kebab” sent me roaring. This is an excellent example of using an anecdote to bridge the gap between your ideas and your readers’ lives. Mark didn’t meander on to tell a story of his late-night kebab search, but worked some of his lived experience (either searching for a kebab himself or watching another chap failing at it) into a point he was making: alcohol makes you more hungry.

When we write on the internet, there’s this urge to show off everything we’re seeing, drinking, and eating while assuming that other people aren’t doing the same thing. With time, this gets as boring as reading through the paragraphs of junk from an over-texter. Whereas, with practice, your personal stories/references could be a palpable punch that collapses abstract ideas into real examples.

But to get to this point, we need a wealth of experiences (both in libraries and life) from which to source these stories. I constantly find myself writing about things that have happened in high school or citing a book I read five years ago, and if I do it right, they will not take up more than two sentences per paragraph. Yet, those two sentences probably took many stupid nights, a dozen books and a stack of journals to distil, and it’s ok. Because in the presence of a strong idea, only writing 10% of your experience is more than enough.

And if you’re struggling with finding a strong idea, let us begin again with (return to lesson 1).

Congratulations 🙌🏽

Congratulations on your 20,000 subscribers, Robin! I am quite sure that you won't be the guy who gets banned from breakfast.