The Theory That Shook Literary Studies To The Core

Part 2: Three Thinkers That Tipped Literary Studies Upside-Down

Housekeeping

I published the last post fully expecting a whole lot of people to doze off at their desk, knock a cup of tea over and start suing me for either personal injury or property damage. None of that happened.

What I received was an overwhelming amount of support. Some of you even wrote that this is the first time you’ve read something from me and that you can’t wait for part two. So, after recovering from a stomach flu (sorry for the delay, folks) and weeks of gathering years of research, here’s part 2, and I’ve decided to remove the paywall from this one as well.

If you weren’t here last week, here's a quick recap. I’m transitioning A Mug of Insights into a free newsletter dedicated to offering people a quality literary education. Paywalls have allowed me to get to where I am, but to get to where I want to go, the newsletter must evolve.

But this vision will take some time, as some posts will still be paywalled. I’m currently working on a project that will allow this dream to happen, but in the meantime, the quickest way to support me is by grabbing a copy of my Notion template if you’re in the market for an efficient and effective digital notebook: The Syntopicon.

Now, with that out of the way, let’s pick up where we left off.

Literary Studies

Ah, that cursed subject where a professor writes a line from a play on the board, picks on me and interrogates: “Do you know why this line is so great, Mr. Waldun?”

“Eh, I’m not sure what you mean, Sir.”

“Well, look closer.” He walks up to me and drags me to the board with my ear in his hand, “Keep looking! Do you see it?”

“See... ouch! See what?”

“KEEP LOOKING!”

All I could see was a description of some guards biting their thumbs at each other. “I’m still not sure what you mean, Sir.”

“Are you challenging me, Mr. Waldun?”

I looked down, pulled out my left thumb and put it in my mouth. “What, this?”

And without warning, he pulled out a gun on me in front of the whole class.

Ok, that didn’t actually happen. But you’re probably just as confused as me when you first encountered the guards biting their thumbs in Romeo and Juliet. Was it a form of greeting? A form of taunting? An invitation for a duel?

During our last little jaunt through the countryside of literature, we ended with I. A. Richards’ Close Reading and explained how it virtually created how English literature is widely taught at schools. Basically, stare at it for as long as possible and you’ll find something! It also championed the idea that innate literary quality can always be perceived if you have well-trained eyes.

But then let’s just say we have some engineering kid taking Shakespeare as an elective. They don’t know who the hell Romeo and Juliet are, they don’t know how to read a play, and they certainly don’t know what biting thumbs meant in that scene. Unfortunately, dragging them up to the board and telling them to look harder will not make them better readers. It’ll only result in a complaint letter and HR shenanigans.

See, the missing piece here is context. Sometimes a good edition of Shakespeare will give you footnotes that will fill in these missing pieces. Sometimes a quick Google search will do, but in most cases, older books make no sense without properly understanding the context around the book (just try Chaucer and you’ll see). So, Richards’ silly little idea of a context-free interpretation is like cooking with an unlabelled spice rack.

The discussion around context might seem obvious to us now, but in the 20th Century, it sparked a bloody all-out war in literature departments. See, right around when Close Reading gained momentum around the 1920s in England, the French across the channel were busy cooking up something else. And this something else simmered and simmered, until it boiled over into a key rival to Close-Reading:

Structuralism.

The debate around Structuralism is as exhilarating as it is complex. Any one of these key moments I’ll write about is worth a full bookshelf of research, and I owe a lot to Peter Barry’s Beginning Theory for giving me a great foundation to work off of. But for the sake of a good story, I’ll not get into the technicalities and avoid jargon when possible. So, without further ado, let us begin with a weird little man named Ferdinand De Saussure.

1: What Do You Mean by Mean? – Saussure Lays the Foundation

When you stare at a passage from a poem or a novel, the first thought will always be: What does it mean? While that English lot with their Close Reading might tell you to read it again, a Swiss had some different ideas at the end of the 19th Century.

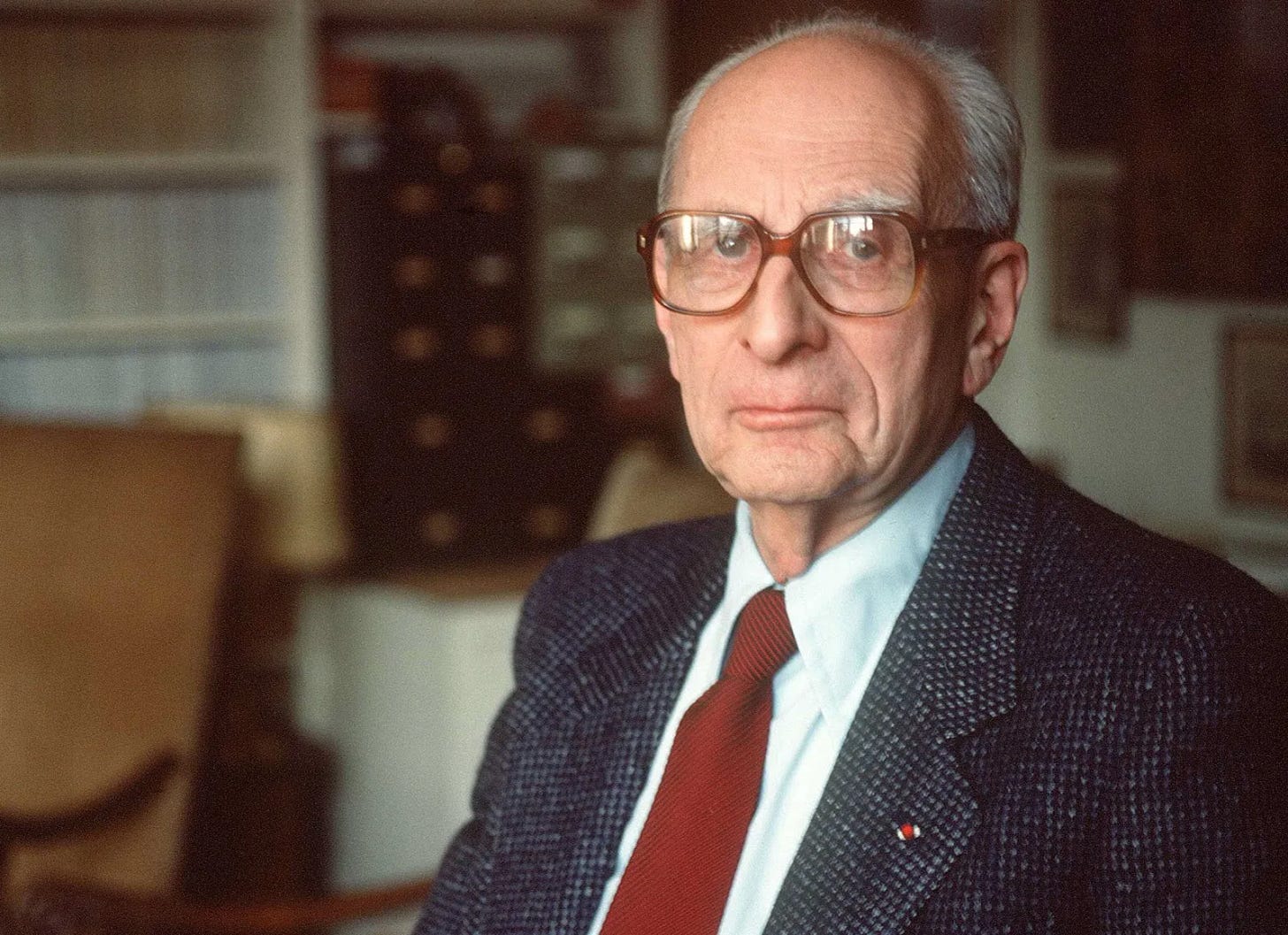

Saussure was a Swiss linguist who boasted a precise and meticulous nature, much like some of the watches made in his home country. He was a bit of a recluse, rarely engaged with his contemporaries and published close to nothing during his lifetime. His only works were some of his lecture notes and monographs, yet this slim output turned our understanding of literature upside-down.

He had two big ideas that destroyed the dream of a context-free close reading:

Firstly, the meanings we give to words are purely arbitrary. There’s no reason why a dog should be called a dog, and if we train a child to call a dog a chair, the meaning will still carry through (just don’t tell him to sit on it). Language isn’t code for some real thing, but it’s a system built on conventions and at times, random associations (take slay! for instance). Meaning isn’t inherent in words but is assigned arbitrarily.

Secondly, meanings from words are relational. This is another way of saying that you can’t define a word without knowing other words that surround it. Selfie doesn’t mean anything if you don’t know what a phone with a camera is. Likewise, the phrase getting trolled on the internet will get you a few sympathetic glances today, but it would send you to house arrest in the Middle Ages. Meaning has to relate to other meanings.

These two ideas dealt two devastating blows to this idea of a close reading without any context.

On the one hand, asking an isolated passage: What do you mean!? after dragging its face out of the toilet is completely impossible. Its meaning is determined by the rest of the novel, if not the entire history of the language. Take our earlier example of biting thumbs from Shakespeare, the meaning can’t be deduced from the play alone, but we’ll also need some history of Elizabethan English etiquette, other evidence of people biting their thumbs and potentially the whole etymology of “thumb” if we want to get nerdy.

On the other hand, just to make things worse, the same passage can mean completely different things to different people. Imagine a French couple: the guy’s a chef and the girl’s a librarian. They both hear the phrase: Notre-Dame de Paris. The guy shrugs, “c'est pas un bâtiment laid (meh, not an ugly building)” while the girl exclaims in excitement “J'adore ce livre (I love that book)!” Then, an American who’s learning French walks by: “Who the hell’s this lady from Paris you two keep banging on about?!”

See, these three exist in three different webs of meaning. The guy thinks the phrase is pointing to the physical Notre-Dame church, the girl thinks it’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo and the American takes it literally: Notre (our) Dame (lady) de (of) Paris (Paris). Are any of them wrong? Or did they just deduce different meanings from their life experiences? Is the difference merely on paper, or does it have something to do with the culture we grew up in?

2: When Nonsense Makes Sense – Levi-Strauss Does the Dirty Work

From the example above, we can see that meaning comes from a web, and each and every one of us has a different meaning-making system that gives different interpretations. But what is that web in our minds, and where did it come from? Enter Levi-Strauss (no, not the jeans guy): the one who put the structure in Structuralism.

Claude Levi-Strauss was an anthropologist who read about Saussure’s ideas, got into a fit of frenzy and decided to apply them in his anthropology work. He ran around to the sites, collected myths and folklores and concluded that individual stories mean nothing if we don’t know the culture around that story. And culture, in this case, is the structure that gives meaning to individual stories.

For example, the Chinese language is known for having these cryptic idioms. A good one is 掩耳盗铃 (yǎn ěr dào líng), and it roughly translates to stealing a bell with your ears covered. It makes no sense, right? But if we take the larger structure of Chinese folklore into account, this idiom came from an ancient story of a man trying to steal a bell with his ears covered. He believed that if he couldn’t hear the bell ring when he touched it, then the owner would also turn a blind eye to his theft. Of course, it didn’t work, and he got busted. Moral of the story? Self-deception. Now this idiom is so ingrained in Chinese culture that most people have forgotten about the story, but hold onto what it meant.

The same applies to English idioms. We know exactly what hit the sack means without knowing what it means, and we won’t call the police if someone’s on their way to break a leg at an audition. But if we take a look at these idioms in isolation, they’re nonsense. And this is the key insight of structuralism: for nonsense to make sense, there has to be a structure of stories, myths and culture around it.

Levi-Strauss ran with this idea and concluded: given that culture is a structure of stories, myths and conventions, it too can be read and analysed like a poem, a novel or a line from the scriptures. What was originally mysterious and aloof can now be decoded, and culture can now be studied rigorously. As a result, something as aloof as fashion can now be studied because it belongs to a structure of power, conventions and transgressions.

This idea was so influential in the 1950s that a bunch of thinkers ran around and looked for these hidden structures that inform how we act, speak and eat. And one of them got so obsessed that he took this structure-hunting to a whole new level. Yes, we’re talking about Roland Barthes.

3: Un Verre du Vin, Monsieur – Roland Barthes on What It Means to Be French

Now, bring to mind a French person. What do you see?

They dress well, they carry flowers around, they smoke cigarettes around the clock, and after a lengthy stroll around the Jardin de Luxembourg, they would settle down to have a wine on the terrace.

Ok, pas mal, and Roland Barthes would be proud of us. What we just did was exactly what he did in his 1957 book: Mythologies.

Barthes was the one to put some suave back into French theory. Up to this point, most structuralists were the type to take a burger apart before eating it. Yet Barthes, with his elegant long coats and cosy scarves, turned his attention to something which has not been subjected to intellectual analysis before: the mythology of everyday life.

With the insights from Levi-Strauss and Saussure, Barthes set out to decode the mythologies that ran the lives of French people in the 1950s. His essays in that collection included an analysis of the difference between boxing and wrestling, an exposition on why steak frites is such a big deal and how soap formed our understanding of “cleanliness”.

Barthes took what was obstruse about structuralism and developed a common language: the individual is contextualised by structure, so anything that we think, do, eat, and smell can be explained by the culture surrounding it. Now, something as mundane as a McDonald’s bag or a Polo shirt with a popped collar can be subjected to structural analysis. They are read as signifiers in a chain of meanings, and this is what we now call cultural studies: an investigation into the structures that made these signifiers work.

Again, all this might seem to us to be common sense, especially for people who write here on Substack. We’re so good at picking a TikTok or an album cover to produce an analysis about culture, media and how we see ourselves. But realise that this is the legacy of Structuralism. The act of going beyond the immediate signifier in search of the structure behind it is a very signature 20th-century French theory move.

So, next time when you’re drafting your think piece, notice that you’re working from a long lineage of structuralists that came before you. And that’s exactly what an influential theory does: it infiltrates our everyday life and truly allows us to stand on the shoulders of giants.

4: So… What’s With the Thumb-Biting?

As our journey today comes to an end, let’s return to what got us into this mess in the first place: the thumb-bite in Romeo and Juliet.

Now that you’re armed with an understanding of Structuralism, let’s put it to the test.

A structuralist’s immediate instinct is to look beyond what’s there. A gesture is never just a gesture; it belongs to a long chain of meanings. While the traditional close-reading approach might get you to just focus on the text, a theoretical or structuralist approach encourages you to look into the history of Elizabethan England, the etiquette at the time and maybe even the socio-economic dynamics that prompted such a fight in the first place.

This key move here liberated many strands of literary thought around the 50s and 60s. Literature was no longer just reserved for tweedy guys hunching over Robert Frost poems. But it was an exhilarating sport that combined philosophy, history, linguistics and even psychology to inquire into our humanities as well as the culture that surrounds us.

Literary studies, then, shifted into an interdisciplinary study and slowly but surely, a theoretical turn started happening around the 1950s that liberated an army of theorists who invented methods of reading that were as innovative as they were controversial. In other words, theory around its peak in the 1980s truly wiggled literature out of the grips of a disinterested and clinical outlook on reading. It’s now filled with energy, discovery and a bit of danger.

Reversal: The Man Who Broke Structuralism

Now, after our little journey through Structuralism, you might think to yourself: what could go wrong? The excitement of reading was back, along with innovative theories, and things looked rather rosy… until an unassuming Algerian French philosopher arrived at the lecture hall of Johns Hopkins University in 1966.

His name was Jacques Derrida, and the lecture he delivered, again, turned how we view literature, theory and culture not only upside-down, but inside-out.

[To be continued]

This was engaging and the discussion of contextualism fair but your description of close reading is a bit of a fantasy. Given the sheer necessity of context to understand the meaning of language, it's inconceivable that any analytical framework would ask for context-free interpretation. That's not what close reading was about. Close reading would presume you start your analysis with a full contextual awareness of the significance of the text but it then uniquely focused on formal properties: given what you know the text to mean, why these words instead of others? Why in this order with this syntax? What resonance do they have with other phrases and ideas in the text? etc. This simply set it in contrast to prior kinds of analysis which dealt only in broad strokes with themes, characters, morals and so on.

Thanks for this! It definitely does address a qualm I had about your mention of Thomas Ford’s fragmentation in a recent video. I disagreed that regarding the whole of a text in general makes for a shallow reading, just because you’ve been interacting with people who spout shallow readings and then can’t point to where specifically in the text they got their interpretation from. When you summarize Ford’s fragmentation, then I understand what it’s getting at…when the alternative is somebody with a shallow reading that can’t pinpoint where in the text specifically that reading comes from, so they might as well not have read it…but then there wasn’t a standard in that summary for exactly how fragmented the poem excerpt must be. A singular word such as “tiger” could have been fragmented from a William Blake poem (“The Tyger”) or a Dennis Cooper poem (“First Sex”) in which the explications about the tiger are very different. In which case, yes, we can’t drag somebody up to the blackboard to meditate upon the word “tiger” until they magically know the profoundness of its literary meaning…because there’s interrelations with all the other words in this word’s respective unit of work (1 poem), and beyond that if that scope is established. (I’m also thinking of a 2023 thesis by Peter Egger, titled 'Tracing Fanwork from Source to Its Furthest Extreme’ that I thought declared an interesting mode of interpretation that rejected both the nitpicky fragmented close-readings as well as the statistical general measure of everything. But what that left appeared to be thematic coding of a handful of specific works, in which case when does that become biased cherry-picking of examples to bolster the thesis statement versus the more understandable discernment of what works are relevant to the thesis? But I appreciated that the scope examined the fanbase activity surrounding three Broadway musicals that I was very familiar with, particularly prose and illustrations inspired by those source materials. I suppose it’s like dots in a constellation, and if somebody else thinking “no that’s not a big ladle, that constellation is a bear” then they had better write their own thesis, throwing shade at the author of the previous thesis in the footnotes, and then maybe that’s how it really goes. )